MITRE CVE-Programm: Die Achillesferse der globalen Cybersicherheit

03.05.2025

Abhilash Hota

Das CVE-Programm (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) spielt eine zentrale Rolle in der globalen Cybersicherheit, indem es eine einheitliche Sprache zur Kommunikation über Schwachstellen bietet. Es wird hauptsächlich von der MITRE Corporation im Auftrag der US-Regierung verwaltet und ermöglicht die schnelle Verbreitung kritischer Informationen. Der Artikel beleuchtet den Ablauf von der Entdeckung bis zur Veröffentlichung einer Schwachstelle als CVE-Eintrag und zeigt die Rollen von MITRE und weiteren Beteiligten auf.

In den letzten Jahren sind jedoch mehrere Herausforderungen deutlich geworden: Die Zahl der jährlich erfassten Schwachstellen stieg stark an – von 6.449 im Jahr 2016 auf über 40.000 im Jahr 2024 – was die verfügbaren Ressourcen stark belastet. Es kam zu erheblichen Bearbeitungsverzögerungen, insbesondere beim NIST NVD (National Vulnerability Database) im Jahr 2023, wodurch viele Schwachstellen über längere Zeit unbearbeitet blieben. Auch die Datenqualität variiert stark: Trotz eines detaillierten CVE-Schemas sind die bereitgestellten Informationen oft unvollständig oder uneinheitlich. Zusätzlich ist das System stark von der Finanzierung durch die US-Regierung abhängig, was Anfang 2025 zu einer potenziellen Unterbrechung des CVE-Betriebs führte. Die zentrale Rolle von MITRE und NIST als Hauptakteure birgt zudem ein hohes Risiko durch mögliche Ausfälle oder politische Instabilität.

Der Artikel schlägt Maßnahmen zur Stärkung des CVE-Systems vor, darunter eine öffentlich-private, internationale Partnerschaft zur Verteilung der Verantwortung, Verbesserung der Finanzierungssicherheit und Reduzierung von zentralen Schwachstellen.

Key Stakeholders and Disclosure Process

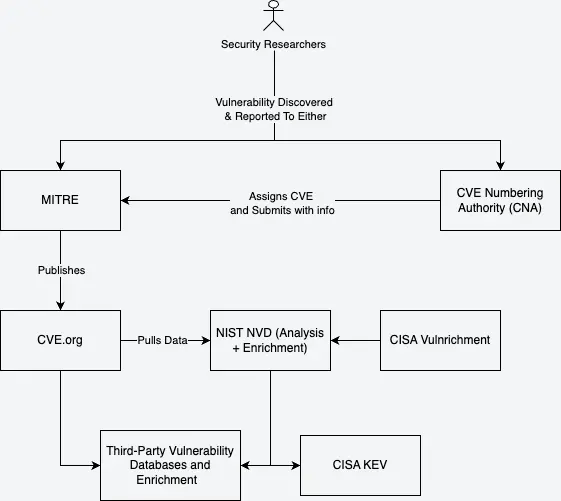

The vulnerability disclosure process primarily involves the following entities:

- Researchers and Discoverers: Initial identification and reporting of vulnerabilities.

- CVE Numbering Authorities (CNAs): Organizations responsible for assigning CVE identifiers.

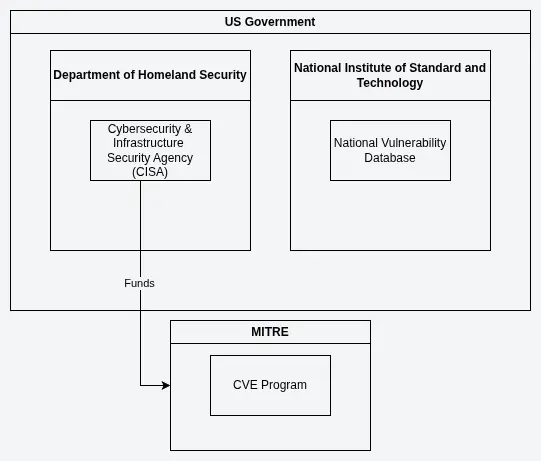

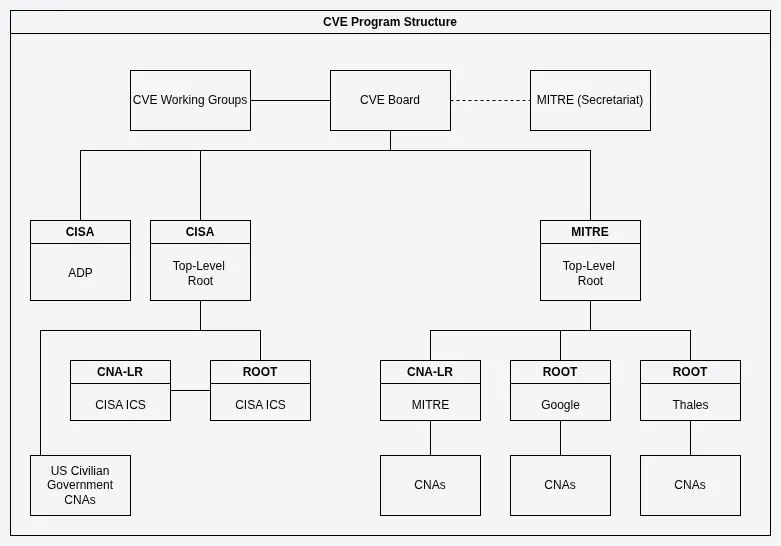

- MITRE Corporation: Manages CVE infrastructure and publication. They receive funding from CISA (~$30 million since 2023) for running the CVE Program.

- CISA and NIST (U.S. Government): Provide funding and additional vulnerability data enrichment via the NIST NVD and CISA Vulnrichment.

CISA and NIST lie within the umbrella of the U.S. Government, while MITRE is a private organization that runs the CVE program financed by the U.S. Government through CISA.

The CVE Program itself has a hierarchical structure, with MITRE and CISA currently serving as the only top-level roots.

The process of discovering and reporting a vulnerability is mainly based on the following steps:

- Discovery: Vulnerabilities identified and reported to vendors or coordinators.

- CNA Submission: CNAs assign CVE identifiers; MITRE generally handles cases lacking appropriate CNAs. However, a security researcher can bypass CNAs and report directly to MITRE.

- Coordinated Disclosure: Information is withheld publicly until mitigations are available.

- Publication: MITRE publishes CVE entries publicly on CVE.org and GitHub.

- Enrichment: The National Vulnerability Database (NVD) gathers public information from CVE.org, provides analysis, and adds data, including CVSS scores, CWE types, and affected products. This database is used by organizations globally for vulnerability prioritization and/or risk assessment.

Key Challenges

In recent years, the CVE system has faced substantial challenges:

- Growing CVE Volume: The annual number of vulnerabilities increased significantly from 6,449 in 2016 to 40,300 in 2024, putting a significant strain on resources.

- Processing Delays: Notable backlogs, particularly at NIST’s NVD in 2023, caused widespread delays, leaving vulnerabilities unanalyzed for extended periods.

- Data Quality Variability: Inconsistent data quality and completeness across different CNAs undermine reliability. While the CVE schema is quite comprehensive, the data provided during initial submission and eventual analysis often leaves much to be desired.

- Funding and Stability: MITRE’s operations depend heavily on U.S. government funding, creating vulnerability to budgetary and political instability. Early 2025 saw the industry facing potentially halted operations in the CVE program due to delayed contract renewals.

- Centralization Risks: Sole reliance on U.S. government-funded programs at MITRE and NIST NVD as the central manager and primary data repository creates a significant single point of failure.

Alternative Vulnerability Databases

Other countries also maintain vulnerability databases and reporting programs. However, they offer varying levels of coverage and maturity.

China (CNNVD/CNVD): China maintains two major vulnerability databases. The China National Vulnerability Database of Information Security (CNNVD) is managed by the China Information Technology Security Evaluation Center and is the primary catalog of vulnerabilities in China. The China National Vulnerability Database (CNVD) is managed by the National Computer Network Emergency Response Technical Coordination Center. While these databases have a high throughput and are quick to publish vulnerabilities, they are completely government-controlled, highly centralized, and have relatively opaque processes.

Japan (JVN): Japan Vulnerability Notes (JVN) is a vulnerability information site operated jointly by the JPCERT Coordination Center and the Information Technology Promotion Agency. It provides descriptions, remediations, and vendor notes on vulnerabilities. JP-CERT is a CNA and works in tandem with the CVE program. While it offers essential local context, it is narrower in scope and relies on the global CVE system for baseline identification.

EU (EUVD): European countries have maintained mainly their own CERT advisories and relied on the CVE program/NVD. However, the EU NIS2 directive in 2022 and the Cyber Resilience Act have led to a push for Europe’s own coordinated vulnerability disclosure program. The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) is a CNA and has launched the European Vulnerability Database (EUVD) as a multi-stakeholder pilot program. However, it is in the early stages of development and adoption.

Proposals for The Future of the CVE Program

We propose the following strategic enhancements as a possible solution:

Distributed CVE Governance: Establish an international, public-private foundation involving global stakeholders, including researchers, industry representatives, and national governments (e.g., national CERTs/CSIRTs).

Diversified and Distributed Funding: Reduce reliance on single-source funding by distributing financial support across multiple governments and private sector partners, ensuring continuity and resilience.

Operational Decentralization: Introduce regional hubs for data storage and operations, expanding the number of top-level root CNAs to balance the analysis workload and build redundancies into the system.

Unified Global CVE Naming Standard: Maintain a single global CVE naming convention to avoid fragmentation and facilitate consistency and communication efficiency worldwide.

Enhanced Transparency and Collaboration: Implement public oversight to build trust in the cybersecurity community.

Conclusion

The CVE program, while somewhat polarizing in certain circles, has been a mainstay of the global cybersecurity effort. That said, as an industry, we must listen to our own advice and not allow single points of failure in crucial systems. This article does not suggest a need for new standards. The underlying program itself has been a net positive and can still play an important role, but how we have structured and administered it needs to change. While the suggested steps require a certain level of political will and a not insignificant amount of negotiations and wrangling, we believe that, in this case, the ends would justify the efforts.